During the last two decades, Japanese society has been subjected to unparalleled social changes. At the same time, Japan has not been the victim of war, revolution, or severe political shifts in this period, with the result that many observers fail to recognize these changes as crucial. There is no doubt, however, that the changes of which I speak represent a drastic impact on our society. If one reflects on the degree to which our lifestyle, technology and social environment have changed in just the last five years, it sometimes feels to have been equivalent to an entire generation.

Among these changes, the rapid development of the information media and their increasing influence is particularly remarkable. Only ten years ago, few ordinary Japanese could imagine that computers would become as influential in daily life as they are today. Consider my own personal experiences: In 1982, I asked my university staff to purchase a word-processor for our office. To my surprise, the request was refused on the basis of the fact that professional typists were employed for producing official documents. When I then purchased a personal computer in 1984, someone asked me why a computer was required for the study of Japanese culture. Such negative responses, or failures to recognize the new technology were not unusual, particularly among the humanities departments of universities in those days.

Today, however, even employment information is delivered through the Internet, and most university staff have begun to feel that they will not survive without introducing computer systems. More and more educational programs and research plans have come to presuppose the use of computers. At the same time, the "consciousness gap" between those who use computers as daily tools and those who refuse to use them has become even greater than the generation gap.

In addition to the wide use of computer, another important change that has occurred is the broad expansion in people-exchange between Japan and other countries. Now, many students and young working women can easily take short informal holidays to countries that most Japanese considered high-tension, "once-in-a-lifetime" destinations only twenty-five years ago.

The sensory distance between nations has also become greatly diminished in recent days, and the mutual influence in our daily lives is accordingly enhanced. Another personal experience: the club to which I belonged in my student days holds an "alumni party" during the course of the university's annual festival. (I might note, by the way, that Professor Nishigaki and I both belonged to the same club.) Just a few years ago it was announced that about ten percent of the alumni of our club now live or reside in foreign countries.

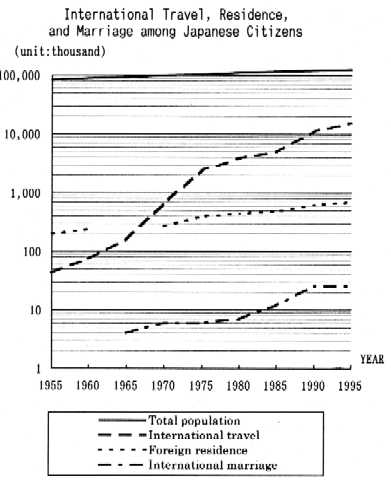

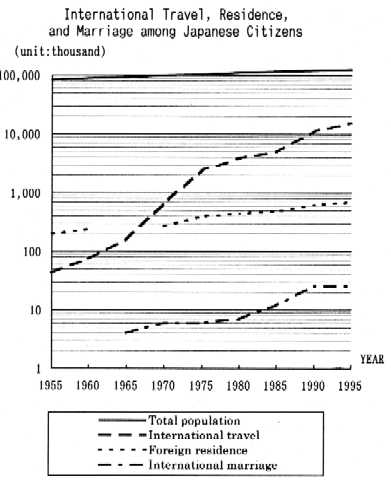

This trend is not merely limited to my own personal experience, as can be seen from the accompanying chart. For example, while only some 660,000 Japanese went abroad in 1970, the number in 1995 was more than fifteen million, representing a jump of about twenty-three times the earlier number. The number of Japanese now living in foreign countries has also increased from about 260,000 to 690,000, an increase of nearly two and one-half times. The number of the persons who marry foreigners is steadily increasing. Japanese people have more chance to encounter foreigners in various situations as a result of the increase in multinational enterprises and students studying abroad. While somewhere over five-thousand Japanese married foreigners in 1970, that number increased to twenty-five thousand in 1994, a five-fold jump.

Another new experience for Japanese is the introduction of Islam. Previously, it was perceived by most Japanese as little more than one more alien religion. Now, however, it is becoming more familiar as the result of increasing numbers of laborers from Bangladesh and Iran. As these countries belong to the Islamic sphere, an increasing influx of people from those countries presents more occasions for Japanese to directly experience the Islamic religious and social customs, including salaam or prayer, as well as food taboos such as the prohibition against pork. So direct encounters with Islamic custom are now occurring in many areas of Japan.

The fact that some of these phenomena have only been noticed recently is in one sense a special result of Japan's geographical characteristics. In other words, the insular nation of Japan has only in recent years been faced with a new dimension of international relationship. Increases in international marriage and the residence of people from Islamic sphere can be understood in this way. At the same time, some of the phenomena to which I referred above are not limited to Japan, but changes proceeding on a global scale.

Similar to the case of Japan, a variety of cultures are now deepening their mutual interchange, but in a "tangling" kind of way, rather than as a matter of systematic order. As a result, no one can presuppose what kind of music, art or sports from which specific ethnic group or nation will next impact what areas of the world. Apart from the prevailing commercialization of major artists' songs, movies or computer software through the strategies of multinational mega-enterprises, unexpected expansion can occur in a variety of other phases merely as a result of customer preference.

As a result, it is difficult for any country to quit itself of this influence race. Given the background of continuously increasing numbers of televisions and computers, a full-scale blockade of information from other countries or societies would demand enormous efforts. The same goes the increase in personal interaction. Only a totalitarian, or militarist government can attempt to minimize global influence in information age.

Taking an example of the East Asian countries, the increase in the amount of information exchanged within the area is now unmeasurable. The implementation of satellite broadcasting represented a particularly decisive turning point in the exchange of information within Asia. Japan launched its BS-2 broadcasting satellites in 1984, thus beginning twenty-four-hour broadcasting, with the first channel sending world news.

Commercial broadcasts were begun in 1991. Since the NHK satellite broadcasts could be received on the Korean peninsula as well, some Koreans reportedly criticized the broadcasts as "cultural invasion by means of radio waves." When watching television in Taiwan, you may notice the broadcast of numerous Japanese programs, including many cartoons and drama, as well as producing their own programs which imitate well-known Japanese programs. This kind of situation, where different countries receive each other's television broadcasts and contribute to mutual influence in programming contents, will likely occur more rapidly in the future.

As a result, in the last twenty years great change has occurred in Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and China as regards mutual perception of neighboring countries and regions. These changes have occurred primarily because ordinary citizens now have access to new means of communication and the mutual exchange of information which formerly was under the exclusive control of governments. When attempting to describe this phenomenon, the concept of "internationalization" might be thought initially appropriate. These changes, however, include aspects that are clearly different from internationalization, for which reason I believe the concept of "globalization" is more apt. The concept of globalization is often confused with that of internationalization, and particularly in Japan, a considerable number of scholars do not distinguish between them. This occurs not because they reject the necessity of using additional concepts, but primarily because they are not familiar with the concept of globalization itself.

Of course, internationalization and globalization share certain process of changes. For example, both terms internationalization and globalization might apply to such phenomena as enhanced levels of communication, higher levels of information and personal encounters, including international or inter-ethnic marriages and business dealings which have extended far beyond the limitations of national boundaries. At the same time, globalization has features making it inherently different from internationalization.

Internationalization is the process whereby each country recognizes the mutual existence and independence of others, attempting to establish deeper connections with those other states. As a result, internationalization can not be avoided by any ethnic group or nation today, and any nation lacking a proper response to internationalization will be left isolated in the world. While domestic confusion might occur as the result of a traditional culture's rapid encounter with other, foreign cultures, the process of internationalization is, in itself, not antagonistic to the existence of individual nations.

The process of globalization, on the other hand, fundamentally includes elements that challenge the structural integrity of states, and might thus even represent a threat to national integrity. When globalization is considered as a "borderless" phenomenon, it is commonly supposed that economic activities or human migration are chiefly meant. The exchange of information on the Internet can be considered a typical process in globalization, involving even a kind of anarchy. The globalization process results in the constant formation of new, but yet-unknown cultural alliances, alliances that differ from those which formerly were established by the nation or specific ethnic groups. As a result, it produces not only convenience but also a vague anxiety. Some scholars observe that globalization process has been present since ancient times, a feasible statement, when one considers the way in which national or ethnic boundaries have extended in religion, technology, the arts and sports for thousands of years. In this sense, globalization is equivalent to internationalization.

In recent years, however, globalization, especially that promoted by the "information age," differs considerably from the former type of globalization, both in its scale and its influence. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the recent kind of globalization has proceeded only after the historical stage of the world-wide establishment of the modern nation-state system.

The modern nation-state involved the establishment of legal and economic systems and the formation of sophisticated cultural forms, and it was aimed at the use of those forms to maintain social order. Each state composed an integral cultural pattern. It adopted one or more official languages, sometimes established official religions, and introduced uniform educational systems. As a result, cultures took on their own unique characteristics based on the unit of nation. The recent process of globalization, however, is challenging this situation.

As a result, the globalization process poses a challenge as well to the ethnic culture contained within each nation. It frequently invades and transforms the forms of indigenous culture which were established by ethnic groups and nations. When successful, the cultural contact of internationalization promotes mutual understanding among discrete nation-states and ethnic groups, and while certain transformations in each culture might coincidentally result, the process of internationalization itself is possible without such transformations. The process of globalization, however, tends to be incompatible with the maintenance of indigenous cultures.

This side of the globalization process might be best expressed as a "stateless condition." Stateless culture means the process whereby cultures are mixed on a global scale. Globalization is a common phenomenon in the areas of technology and business. New technologies are instantly shared by multiple companies and nations. The emergence of multi-national companies promotes complex production processes wherein almost no one knows what nation or people are involved in the making of a new car, computer, or other product.

At the same time, it is commonly considered that phenomena related to ethnic culture are much more conservative than those related to technology or business, since an orderly way of life becomes difficult when the language, characteristics, religions, ethics, families and value systems of a society are subject to incessant change. Despite this fact, the globalization process can now be seen advancing even in those areas deeply concerned with ethnic culture.

Based on the perceptions noted above, we have selected three specific themes that we hope will allow us to debate the globalization process as it is related to the cultural dimension. Those themes are religion, language, and family and community. While religion is no stranger to the globalization process, the cultural features of family, community, and language are thought to demonstrate strong resistance to the processes of globalization. But while these cultural elements represent conservative aspects of an established social system, they cannot escape from the globalization process, thus resulting in changes in traditional forms.

Of the three areas, the globalization trend in religion is observable in a variety of ways. On the one hand, traditional religion is frequently said to be in crisis, secularization is pointed to, and the irreligious tendencies of younger generations are mentioned; on the other hand, new religious movements are springing up throughout the world, rapidly extending their influence. It is not unusual to find that the majority of adherents in new movements are young people. Various types of fundamentalism are advancing even in the Western world, where the trend toward secularization was strongly proclaimed in the 1960s. This suggests the need to reexamine the way in which religious power easily oversteps national boundaries.

Why is this kind of phenomenon occurring? Where are these tendencies oriented? These questions suggest a substantial problem, while we can point out partial characteristics of the globalization process, we should consider how religion, originally oriented toward globalization, will display new developments in the information age.

Likewise, each nation experiences its own problems in the area family and community. The increase in international marriages and inter-ethnic marriages serve as the occasion for various new difficulties. Local communities frequently fail to function well at the role of transmitting community traditions among their members as a result of changing styles of life. Consequently, gap widen in both consciousness and behavior patterns between the generations. Family and community systems are also influenced to change due to the effects of globalization in the areas of personal mobility and access to information.

For example, in East Asian countries, the family and community have been traditionally located in a relationship of intermediate concentric circle vis-a-vis the individual on the inside and the state on the outside. That is to say, the family formed the smallest unit of individual association, the community formed the unit of associating families, and the state formed the organic unity of communities. It was for this reason that Confucian ethics expressed this relationship as the "morality of the individual, the economy of the family, the rule of the state, and the stability of the world."

The globalization process, however, threatens to gradually collapse this concentric structure. And this threat is different from that which confronted the family and community in the earlier process of modernization. In modernization, change to family and community occurred in conjunction with advancing urbanization and industrialization. People migrated from rural areas to urban areas as a result of industrialization, and village communities were frequently faced with a crisis of total collapse. Urbanization promoted the increase in nuclear families, and the priority given to company activities led to the phenomenon of separated families, where the main laborer was frequently assigned to posts forcing him to live separated from his family.

This process, however, did not change the ideal image of the traditional family or community. In fact, the situation was one in which family members and village communities were being unwillingly forced to endure extraordinary conditions. As a result, the process of modernization always assumed an orientation pointing back to the traditionally envisioned structure of family and community.

The advancing wave of globalization, on the other hand, challenges the fundamental structure of family and community itself. Globalization will bring about an increase, even in East Asia, of families composed, for example, of a Chinese father, Japanese mother, and bicultural child who works for a company in the United States. This will bring about drastic changes of consciousness regarding the family and community. Individual members of a community may possess different social values and family concepts, and live under different legal systems. Under such circumstances, it may become difficult to look to the family as an integral part of the community unit.

In the case of language, the chief problem at present is how to correspond to the age of internationalization. Foreign-language education can be considered a crucial response to internationalization. Formerly, Japanese who assumed that speaking English formed a basic criterion for "being an international person" were often criticized cynically. Now, however, few people assume that "foreign language" always means "English." In the condition of internationalization, more people tend to feel that it is indispensable to learn a foreign language in order to be able to understand foreigner people. This is leading to a considerably complicated situation. A conference held with simultaneous interpretation between panelists speaking ten different languages will require ninety persons for the job of interpretation alone. Interpretation between one-hundred languages involves nearly ten-thousand possible combinations. As a result, each country must educate people who can speak an enormous number of foreign languages if the nation wishes to deepen mutual understanding with all countries and ethnic groups.

On the other hand, globalization may also stimulate formation and development of artificial languages such as Esperanto. At present, so-called "international English" functions partly in this role. Neither British nor American, international English is similar to "pigeon English" in seeking to achieve basic communication. In this sense, we may see a tendency to emphasize basic and accurate communication above other considerations, thus leading to a deemphasis on complicated accents, grammars, or idioms found only in literature. In this sense, how English is utilized and transformed in the age of the Internet may suggest future problems for the role of language in globalization.

One topic limited to East Asian countries involves the future role of kanji or Sino-Japanese characters. At present, mainland China uses a simplified form of the characters, Taiwan uses the classical forms, and Japan uses a combination, or intermediate form. The two Koreas once stopped teaching kanji in schools, although South Korea has started a program of teaching kanji once a week in primary schools. Since the Sino-Japanese script is based on ideograms, it might function as a form of elementary visual communication among societies belonging to the former Chinese-language sphere, and among ethnic Chinese living in Southeast Asian countries. A certain degree of communication is possible by the written form of kanji alone, if the language is taught in each of those countries. This situation might thus be conceptualized as a problem of "local globalization."

A consideration of such problems leads to deep concerns regarding the future development of religion, the family system, community and language in various indigenous cultures, as well as the issue of how each culture responds to those developments.

In addition to the three topics discussed in the symposium, globalization is visible in virtually every sphere of culture. On the one hand, the challenge to traditional and indigenous cultures means the crumbling of former patterns, while on the other hand, it means the start of new, global competition among a plurality of cultures. What will results will be formed there in the area of human relationships, principles of communication, and other basic human values?

What types of relationship will come to exist among complicated cultures throughout the world? Since the competition will occur frequently in a disorderly way and with no specific ethnic background, the process may be both constructive and destructive. The creation of a new tradition on a global scale, or the collapse of culture as we know it.

Of course, many movements have risen in the attempt to resist globalization, aiming for the protection of traditional culture among minorities, the maintenance of local ethnic languages, and the revitalization of traditional cultural forms. While this type of movement appears in conjunction with the process of globalization, the latter movement will inevitably prove stronger. In the face of this prospect, we should recognize the need to foresee what kind of influence globalization will bring about, or what kind of results may be in store.

Nations and ethnic groups are formed from patterns of culture, including manners of eating, rules for the socialization of children, proper ways of greeting, language rules, methods of communication, methods of leading and organizing people, and so on. The fact that people frequently experience so-called "culture shock" when visiting foreign countries reveals that their own culture has become so natural to them that they fail to recognize it as a single, particular culture. Faced with "strange" manners, they realize that their own common sense is not universal.

In the process of internationalization, people make the attempt to understand foreign cultures, alien ideas, different behavioral patterns, and thus recognize differences among cultures. Regardless of the complications involved and friction frequently occasioned, the process itself presents a certain kind of rule. In the process of globalization, however, similar problems occur, but the interaction tends to be anomic, in a situation which might be called one of "free competition." At times, the strategy of multi-national enterprises with enormous capital reserves overwhelms the situation, while at other times, minor folk customs or forms of life may spread and be accepted rapidly throughout the world, as suggested by the spread of tattooing or "skin-heads" fashions.

Globalization thus suggests the advent of many troublesome problems. Among them, one of the biggest is the fact that the ethics or moral systems which have been sustained by each culture tend to be rendered meaningless or rootless. In Japan, for example, traditional values such as politeness, shame, or avoiding causing trouble for others in the community have been almost entirely lost among members of the younger generations. This loss does not result because of a conscious resistance to those values, but because the younger generation was not made familiar with these values. The loss of value is not a problem limited to Japan. A similar tendency seems to be occurring in other cultural areas, with similar rationale.

Crimes like murder and theft are prohibited in every culture, with the result that values concerning such behavior are not likely to change greatly with globalization. Other values may differ considerably between cultures, e.g., the importance given to individual or group, the value of eloquence or silence, and the different values given to simplicity or opulence in styles. No universality can be claimed for the particular values of any one culture, since in the age of globalization, any such claims will be severely challenged by each other culture.

In sum, each society will face many troublesome situations together with the rapid change in traditional and indigenous cultures. And as a result, we will be unable to avoid facing the question of global choice --- which trends may be permitted and which may not --- in coming years.