In Taiwan, as in many other parts of the world, what has happened to its languages and cultures in the past century can be briefly summarized in a simple statement: many indigenous languages and cultures are quickly being diluted because of the fast expansion of the majority language in the country, or the so-called languages of wider communication (LWC), English in particular. The government often justifies its policy and practice in the name of national unity and modernization. In other words, it propagates the majority language for the purpose of achieving national integration and lets the LWCs make inroads upon the indigenous languages and cultures so as to enable its people to gain access to the world of technology and science, and thereby further develop its economy.

At the time, such a sacrifice was seen to be a necessary price to pay, but recently in Taiwan as well as in some other places, people have learned the hard way to see things differently. But before we get to this change, let us first take up what miserable plight the indigenous languages and cultures are in today.

Taiwan is a multi-lingual, multi-ethnic country, composed of four major ethnic groups. According to Huang (1993), the ethnic groups and the population percentage for each group are as follows: the aborigines (speakers of Austronesian languages) 1.7%; Hakka 12%; mainlanders 13%, Taiwanese (Southern Min speakers) 73.3 %. Although the Taiwanese group is by far the largest, Mandarin has been, for historical reason, the national language. Most mainlanders spoke languages other than Mandarin when they migrated in and around 1949 with the Nationalist government, although some of those languages are mutually intelligible with Mandarin. The younger generation coming from these families, however, have switched to Mandarin. Southern Min and Hakka are related to Mandarin as they all belong to the Han language family. Nevertheless, they are not mutually intelligible with Mandarin, and neither are they intelligible to each other.

The aborigines can be further divided into two major groups, the Ping-pu (plain) group and the Gaoshan (mountain) group. The former falls into eight tribes: Ketagalan, Kavaland, Taokas, Pazeh, Papura, Babuza, Hoanya and Siraya and the latter into nine tribes: Ami, Paiwan, Puyuma, Saisiyat, Yami, Atayal, Bunun, Rukai, and Tsou. The eight Ping-pu tribes have almost totally disappeared in the course of the past hundred years, the only exception being the 250 Gavaland speakers living now in Hualian country in the eastern part of the island. The Gaoshan (mountain) group simply because most of them live in the mountain areas have been better able to preserve their languages and cultures, but there are strong indications that both the languages and the cultures are fast disappearing as well.

Since the lifting of martial law in 1988, one hears almost daily reports of the dilution of the three indigenous languages and cultures. Being the minority group, the aboriginal people are in the worst plight. To give just one example, two reports and a commentary on the aboriginal people were published in the China Times on October 25, 1994. The first report is about the Atayal festival dance held in the remote town of Jianshi (Sharp Stone) in Hsinchu country. The activity was sponsored by the town government as part of their effort to preserve the Atayal traditional culture. In the festival many elder people had to teach almost from scratch the young tribemen how to do the festival dance.

The second report is even more shocking. It was reported that proportionally more child prostitutes come from aboriginal backgrounds than from any other ethnic groups. A survey by a Yunlin asylum that gave shelter to eighty-eight child prostitutes in the previous month (September, 1994) found that twenty-two were aborigines, including thirteen from the Atayal tribe. And to top the tragedy, most of them were forced into prostitution by their own parents. Although the reports didn't state it explicitly, it is quite clear to most readers that these cases are the result of the failure of education, and of cultural bankruptcy.

The third commentary actually drew a similar conclusion and strongly urged people to extend their love and concern to these disadvantaged people and to take some effective measures to promote their education and economy.

Language erosion is even more easily spotted. In a recent paper on the sociolinguistic history of the Gavaland Pingpu tribe, Huang and Chang (1995) report that nearly ten thousand Gavaland speakers lived in the I-lan area around 1650, but by the time Professor Ruan did his field work there in 1969, only about eight-hundred speakers were left. Even if we include the number of people who migrated to Hua-lian, the total could not exceed two thousand. But today, less than thirty years later, even the eight-hundred speakers have disappeared, leaving the I-lan area with no Gavaland speakers at all.

The Gaoshan group, though luckier than the Pingpu group, being protected by the mountains, are actually not doing too well. According to statistics released by the government in 1989 the populations of the nine tribes are as follows:

| Amis | 129,220 | Atayal | 78,957 | Paiwan | 60,434 |

| Bunun | 38,627 | Puyuma | 8,132 | Rukai | 8,007 |

| Tsou | 5,797 | Saisiyat | 4,194 | Yami | 4,335 |

And according to Huang's calculations (1991, 1993) based on a questionnaire survey of aboriginal college students, the attrition rate was estimated to gbe 15.8 percent over two generations, and 31 percent over three generations. If Huang's estimates are not too off the mark, almost half of the existing aboriginal languages are going to disappear from Taiwan very soon.

Similar results were also obtained in Lin's 1995 survey report. After surveying one thousand junior high school students in twenty-five schools, Lin found that for the aborigine students, only 37 percent respond that their aboriginal language is the one most frequently spoken at home. Only 68 percent claim that they can speak their parents' language, and among the latter group, only 16 percent claim fluency.

The Hakka students performance was only slightly better than that of the aborigines, with 40 percent of the students surveyed saying that Hakka is the most frequently used language at home. Elsewhere, according to Huang's 1993 survey of 327 Hakka students in the Taipei area and 404 Hakka Taipei citizens, only 70 percent of those whose parents are both Hakka speakers claim that they can speak Hakka.

As for Taiwanese, both Huang's and Lin's survey results indicate signs of erosion, although the rate is relatively slow. Furthermore, Chan's study (1994) shows that the domains traditionally attributed to Taiwanese, such as the home and marketplace are shrinking, indicating that the suprapowerful language, Mandarin, has made inroads upon it as well.

Based on an island-wide telephone survey of 934 subjects conducted by the Formosa Cultural and Educational Foundation, the relationship between the proportion of subjects claiming to be of Hakka ethnic group, and that of subjects claiming to have Hakka as their mother tongue, plotted across three age groups, is shown in Table 1.1

| I Ethnic group identity (%) |

II Mother tongue identity (%) |

III II / I (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| L (18-30) | 7.4 | 5.7 | 77 |

| M (31-40) | 13.5 | 12.2 | 90 |

| H (41-50) | 11.9 | 10.6 | 89 |

Table 1 clearly indicates that the erosion of the Hakka language has intensified among the younger people (those aged below 30, with the erosion rate reaching a dramatic thirteen percent.

For comparison, consider corresponding figures from the Taiwanese group shown in Table 2.

[N.B. Figures in Column I and II refer to the percentages of subjects so claimed in that age group of total survey population and those in Column III are the percentages obtained by dividing the figure in Column II by that in Column I.

| I Ethnic group identity (%) |

II Mother tongue identity (%) |

III II / I (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| L (18-30) | 80.2 | 70.8 | 88 |

| M (31-40) | 76.9 | 74.2 | 96 |

| H (41-50) | 79.6 | 79.1 | 99.4 |

From Table 2, it is quite clear that the Taiwanese group shows signs of erosion as well, although the rate is slower, being eight percent between the mid- and low-age groups, as compared to thirteen percent for the Hakka group.

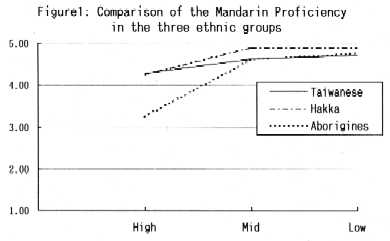

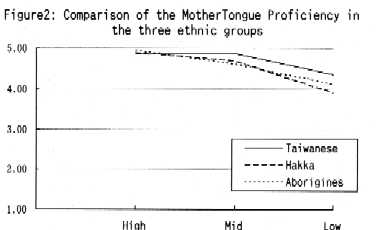

Our own survey based on 2338 valid questionnaires (640 from aborigines, 255 from Hakka, and 1698 from Taiwanese) produced the following results, based on respondents' self-estimate of mother tongue proficiency.

| Language Proficiency | Age | All questionnaires | Ethnic groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taiwanese | Hakka | Aborigines | |||

| Mandarin | H | 3.93 | 4.28 | 4.27 | 3.25 |

| M | 4.73 | 4.64 | 4.90 | 4.64 | |

| L | 4.80 | 4.73 | 4.90 | 4.78 | |

| Mother Tongue | H | 4.91 | 4.85 | 4.91 | 4.96 |

| M | 4.73 | 4.87 | 4.70 | 4.62 | |

| L | 4.13 | 4.35 | 3.92 | 4.13 | |

The results can be more clearly seen from the following two graphs. in Figures 1 and 2. These statistics unmistakably show that all indigenous languages in Taiwan are eroding, with the aboriginal languages diluting at the fastest pace, Hakka close behind and Taiwanese in third place. With the languages gone, the cultures will not stay. So even though the erosion of a culture is much more difficult to quantify because it embraces all aspects of life, we can safely infer from the rate at which languages are diluting that the cultures must be disappearing as well.

As we briefly mentioned earlier, the erosion of the indigenous languages and cultures is due to compounding effect of two forces: the improper propagation of the national language and the global expansion of LWCs. We will take up both in the following sections.

As Romaine (1995: 242) has rightly pointed out,

The traditional policy, either implicitly assumed or explicitly stated, which most nations have pursued with regard to various minority groups, who speak a different language, has been eradication of the native language/culture and assimilation into the majority one.

Taiwan is no exception. Although this policy is nowhere to be found in written form, all signs show that it has been assumed all along. So when some open-minded scholars such as Hong Yen-chiu spoke up for the minority people and argued against a hard-line approach, he was immediately attacked by many hard-liners who criticized that his approach would not lead to national unity (Hong 1978).

In fact, such a high-handed, hard-line approach to the propagation of Mandarin was very prevalent up to ten years ago. Romain (op. cit. 242) reported that in Australia, the United States, Britain and Scandinavia, minority children not too long ago were still subjected to physical punishment in school for speaking their home language. In Turkey where Kurdish is a minority language whose existence is not recognized, the situation was even worse. Thus one Kurdish woman who attended a special boarding school provided for Kurdish children described her heartbreaking experience vividly (Clason and Baksi 1979: 79, 86-7, translated by Skutnabb-Kangas 1984: 311-12):

I was seven when I started the first grade in 1962. My sister, who was a year older, started school at the same time. We didn't know a word of Turkish when we started, so we felt totally mute during the first few years. We were not allowed to speak Kurdish during the breaks, either, but had to play silent games with stones and things like that. Anyone who spoke Kurdish was punished. The teachers hit us on the fingertips or on our heads with a ruler. It hurt terribly. Thats why we were always frightened at school and didn't want to go.

Many short articles, appearing in Lin's 1983 collection of essays described the similar experience many indigenous language speakers had in their early years of school life.

Not only that. Many indigenous languages speakers were informed by their teachers that their languages were base and vulgar and that they should feel ashamed for being speakers of such languages.

In the area of newspaper and electronic media, the control was equally oppressive. Newspapers were exclusively in Mandarin, with one or two English papers being the exception. In the fifties, soon after the Nationalist government moved to Taiwan, it was stipulated that, in view of the fact that most people did not know Mandarin, Taiwanese programs in electronic media would be allowed on condition that they were to be gradually replaced by Mandarin programs. In the seventies, it was further stipulated that programs in the "dialects," meaning Taiwanese and Hakka ,can could be aired only one hour every day. The ban was in effect for about ten years before it was finally lifted together with the lifting of martial law.2

Under the double oppression of school education and the mass media, it would indeed be odd for the indigenous languages and cultures not to die out.

On another front, the indigenous languages and cultures face the relentless competition of LWCs, especially English. Most people know only too well that if one wants to get ahead of others in the world, a good knowledge of English is a necessity. In connection with the preference for English in nineteenth century Wales, William (1986: 514) points out that the slogan was, "If you want to get ahead, get an English head." This is unfortunately still true at the end of the 20th century in Taiwan as in many other places of the world. A prevalent feature of families in Oriental culture is the desire to provide children with everything they need so that they can get ahead, with the result that one finds thousands of parents sending their children to study English to provide them with a headstart, even before English instruction begins at the first year of junior high school. As a result, English schools for children mushroomed in the eighties2, despite the fact that they were still banned by law. 3

Recently, with the advent of long-distance electronic communication such as electronic mail, computer networks and the National Information Infrastructure in the U.S., a new surge of zest for English has arisen. Because it is so recent, its impact on the society has yet to be seen but I can say with certainty that it will do even more harm to the indigenous languages and cultures if no effective measure were taken to protect them.

As we said earlier, the government has long neglected the indigenous languages and cultures with the dire consequence that many of them are fast diluting, creating at the same time many social problems such as prostituting, alcoholism, broken families .4

Fortunately, after the lifting of the martial law, many scholars and common people have spoken up, calling for the use of indigenous languages in education and indigenous perspectives in teaching materials. Government agencies have also responded.

New measures have been enacted to guarantee rights. In 1992, the Second National Assembly amended a constitutional article to ensure "legal protection of [the aborigines'] status and the right to political participation." The Amendment also requires the government to "provide assistance and encouragement to their educational, cultural preservation, social welfare and business undertakings." A law approved by the Legislature this year () 1996 allows the aborigines to restore their traditional tribal names.

Other government programs also assist aborigines. The Ministry of the Interior for example in 1992 launched a six-year program, allocating eight million dollars (U.S.) to promote culture and subsidize medical care. The Ministry of Education also launched programs to promote aborigine culture and fund research on the tribes. It has also announced that beginning with the 1996 School year one period every week will be allotted in the elementary school curriculum for the teaching of the indigenous cultures or languages.

While I have no doubt that many of these programs will bring help to the indigenous ethnic groups, especially the aboriginal people, the thing that worries me and many other researchers (see Mei ,1995 for example) is whether these measures are effective. After studying the Ministry of Education's five-year plan for improving and developing education for the aborigines, I cannot but feel daunted by the scope and the number of projects that the plan has included (Council on Educational Research, Ministry of Education, 1992). In the year 1994 alone seventy-seven tasks were listed. Even though I am in no position to give an overall evaluation, my informed guess after studying all the tasks listed is that only a very small portion of the tasks were actually completed or launched that year.

Actually I agree with Mei (1995) and Liang (1994) that to provide better quality education is probably the most important help that the aborigines need for the moment. The reason is not far to seek. Only good quality education can help these people stand up and take care of themselves as well as others. Unfortunately, the educational improvement program just described is much too little, too late. How much help one-hour of teaching in the language or culture starting at the third grade can do to preserve the fast diluting languages and cultures is anybody's guess. We have had enough empty talk and impractical programs! We need some kind of more radical and fundamental change in the system if we really want to preserve the indigenous languages and cultures.

In order to be effective in helping preserve the indigenous languages and cultures, I have proposed in several previous articles (Tsao, 1994, 1995a, 1995b, 1995c, 1996) that the teaching of the vernacular languages should be started in kindergarten, and that vernacular languages should be used in the teaching of the national language, Mandarin and other subjects until students' command of Mandarin is good enough to use it as a medium of instruction. As I have dwelt on the strengths of this proposal elsewhere (Tsao 1995c), I will simply summarize my main points.

Educationally, the specialists who met in 1951 under the sponsorship of UNESCO (Fishman 1968) unanimously agreed that the mother tongue was the best language for literacy. They also strongly recommend that the use of mother tongue in education be extended to as late a stage as possible, Our proposal is in full agreement with their recommendation.

Also it has been proven by experience (UNESCO Meeting of Specialists, 1951,1968) and by experiment (Ramirez, Yuen and Ramey, 1991) that the teaching of a mother tongue in the way proposed will not slow down students' acquisition of a national language.

Socio-politically, we have cited evidence to argue that the teaching of the vernacular not only will not impede national integration, it will actually help us achieve the vertical integration which is needed in a true democracy.

Finally, as far as the economy is concerned, we pointed out that since we need a great many skilled personnel in our workforce for further economic development, we need to provide the best education to our own citizens, and the most effective way of doing that is through the teaching of the vernacular languages in the early years of school. As Taiwan's economy has produced surpluses, the costs that this system entails will be well within the bounds that it can afford.

Needless to say, I am confident that if our proposal is adopted and put to work, it will go a long way in helping the preservation of the indigenous languages and cultures, not only in Taiwan but also is places where similar situation exists. However, as school is only one social institution having to do with the preservation of language and culture, we should avoid the naive view that school education is a panacea for social ills, As Romaine (1995: 285) has rightly pointed out:

It is probably not possible for a state or one of its institutions such as the educational system to save a shrinking linguistic minority on its own. Only the minority itself can take the decision to adopt appropriate measures to protect themselves.

I would therefore end this paper with a strong plea to all indigenous speakers to forget the differences between them and to unite to fight for their right to their own culture and well-being.

1. The whole report can be found in Tsao (1996), Appendix 7.

2. For a detailed account of language control in the mass media, see Huang 1993.

3. Accounting for Li's (1988) study, the ads for those English schools appearing in the Mandarin Daily News each day increased rapidly. In 1981 only twenty seven were seen, then eighty-three in 1985, and finally one-hundred and three in 1988.

4. For a report of the social problems confronted by minority peoples, see Lin, 1995.

Barnes, Dayle. 1974. "Language Planning in Mainland China: Standardization," Fishman, J.W. ed., Advances in Language Planning. The Hague: Mouton, pp.457-80.

Chan, Hui-Chen. 1994. "Language Shift in Taiwan: Social and Political Determinant." Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation. Washington D. C.: Georgetown University.

Clason, E. and Baksi, M. 1979. Kurdistan Om Fortryek Och Befrielse kamp, Stockholm: Arbetarkultur.

Council on Education Research, Ministry of Education. 1992. Research Projects on the Education of the Aboriginal People: Summary Report.

Edwards. J. R. 1981. "The Context of Bilingual Education". Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 2: 25-45.

Edwards, John. 1985. Language, Society and Identity. Basil Blackwell.

Fang, Zu-Shen, Feng-Peng Zheng and Xiao-Yu Zhang. 1972. "A Brief History of the National Language Movement in the Past Sixty Years." Cheng Fa-ren (ed.) Chinese Studies in the Past Sixty Years. Taipei: Zhengzhong, pp.461-554.

Fang, Shi-duo. 1965, Fifty Years of the Chinese National Language Movement. Taipei: Mandarin Daily Press. (in Chinese)

Fishman, J. (ed.) 1968. Readings in the Sociology of Language. The Hague: Mouton.

Hong, Yen-Chiu. Remarks on Language. Taipei: Mandarin Daily News Press.

Huang, S. F. 1991. "Some Sociolinguistic Observations On Taiwan." The World of the Chinese Language. 7.6: 16-22.

Huang, S. F. 1993. Language Society and Ethnicity. Taipei: Crane.

Huang, S. H. and Z. C. Chang. 1995. "A Sociolinguistic Investigation of Gava land: An Aboriginal Language." Li. R. and Y. Lin (eds.) Collection of Paper on the Austronesian Languages in Taiwan. Council on Educational Research, Ministry of Education. pp. 241-256.

Li, Cheng-ching. 1988. "It is Time to Do Planning in the Teaching of English in the Elementary School." Min-sheng Daily. 2,1,1988.

Liang, Ming-hui. 1994. "Be Earnest in the Effort to Solve the Problems of the Aborigine." China Times. 5, 23, 1994: p.17.

Lin, Diana, 1995. "Aborigines strive to Revive Fading Culture," The Free China Journal. March 17, 1995: p7.

Lin, Jin-hui. Ed. 1983. Papers on Language Problems in Taiwan: An Anthololgy. Taipei: Taiwan Arts and Literature (Taiwan Wenyi Zazhishe).

Lin, Jin-Pao. 1995. "Mother Tongue and Cultural Transmission." Li,R. and Y. Lin (eds.), Collection of Papers on the Austronesian Languages in Taiwan. Council on Educational Research, Ministry of Education, pp.203-222.

Liu, Wei-zhi. 1992. An Ethnological Study of the Multi-cultural Education in an Aboriginal School. Unpublished Master Thesis, Research Institute of Education, National Taiwan Normal University.

Mackey, William F. "Bilingual Education and its Social Implications." in Edward, J. (ed.), Linguistic Minorities Policies and Pluralism. London: Academic Press, pp.151-177.

Mei, Kuang. 1995. "Review of the Current Minority Language Policy in Taiwan." To appear in the Proceeding of the Conference on Current Language Problems in Taiwan. Department of Chinese, National Taiwan University.

Paulston, C. B. (ed.) 1988. International Handbook of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education. New York: Greenwood Press.

Paulston, C. B. 1992a. "Linguistic Minorities and Language Policies: Four Case Studies." In Fare, et. al. (eds.): pp.55-79.

Paulston, C. B. 1992b. Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Bilingual Education. Clevedon, Avon: Multilingual Press.

Ramirez, J.D., Yuen, S.D. and Kamey, D.R. 1991. Final Report: Longitudinal Study of Structured English Immersion Strategy, Early-exit and Late-exit Programs for Language-minority Children. Report submitted to the US Department of Education, San Mateo, CA: Aquirre International.

Romaine, Suzanne, 1995. Bilingualism (sec. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Blackwell.

Skutnabb-kangas, T. 1984. Bilingualism or not: The Education of Minorities. Clevdon, Avon: Multi-lingual Matters.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. 1988. "Mulitilingualism and the Education of Minority Children." In Skutnabb-Kangas and Cummins (eds.), pp.9-44.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T, and Cummins, J. (eds.) 1988. Minority Education: From Shame to Struggle. Clevedon, Avon: Multilingual Matters.

Tsao, Feng-fu. 1994. "Linguistic Adjustment and Social Change." In Papers on the Current Language Problems. Huang, P.R.(ed.) pp.25-52. Department of Chinese, National Taiwan University.

Tsao, Feng-fu, 1995a. "On the Minnan Mother-tongue Education in Taiwan," Newsletter of Center for Taiwan Studies 5 & 6: 1-12. Center for Taiwan Studies, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, National Tsing Hua University.

Tsao, Feng-fu, 1995b. "The Teaching of the National Language and the Mother Tongue in Taiwan." Paper presented at the International Conference on the Chinese Languages in Hong Kong after 1997. Shatin, Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Dec. 9-11. 1995. (To appear in the Proceedings)

Tsao, Feng-fu, 1995c. "Language in Education in Taiwan: A Critical Review in Sociolinguistic Perspective." Paper presented at International Language in Education Conference, University of Hong Kong. December 13-15. 1995. (To appear in the Proceedings)

Tsao, Feng-fu, 1996. Ethnic Groups, Languages, and Policies: A Comparison of Mainland China and Taiwan. Research project report submitted to the National Science Council, ROC, July 1996.

Tse, J.K.P. 1982. "Language Policy is the Republic of China." in Kaplan, R.B.(ed.), Annual Review of Applied Linguistics. Rowley, Mass.: Newbary House 33-47.

Tse, John. K.P. 1987. Language Planning and English as a Foreign Language in Middle School Education in the Republic of China. Taipei: The Crane Publishing Co.

Unesco Meeting of Specialists, 1951, 1968. "The Use of Vernacular Languages in Education," in Fishman, J.(ed.), Readings in the Sociology of Language. The Hague: Mouton, pp.688-716.