Historically, the Christian religions played a very important role in the different countries of Europe. For centuries, political power was directly connected with one or another of, most especially with the Roman Catholic Church: kings and emperors were consecrated in a cathedral by a bishop; the public and civil laws duplicated the religious ones, especially in familial matters. The religious authorities were sometimes themselves the political power as for instance in Italy and in the "Holy Roman Empire of the Germanic Nation," where different component regions were governed by a "Prince-Bishop." All this explains also that in addition to being a political power, the (Catholic) Church was also a very important economic power, owning large rich properties all over Europe. This helps towards an understanding of the Latin maxim "cujus regio, ejus religio," which underlines that to belong to a region was also to belong to a religion. And if, following a war, a region went over to a prince whose religion was different from that of the defeated prince, the population was expected to change its religion and to adopt the one of its new sovereign.

With the differentiation which modernity introduced and the process of secularization which resulted, the religious field became more and more specific and the political, legal and economical domains began the develop their own rules. This transformation was very slow and affected the diverse European countries differently and with a various impact. France, which before was called "the eldest daughter of the Catholic Church,"went furthest after the 1789 Revolution by proclaiming the state a "République laïque."Other countries, like Belgium or Germany, also proclaimed in their fundamental law the separation of religion and state but it is clear that religion still plays there an important although unofficial role. In Belgium, for instance, every important national event is marked by a Catholic celebration: more than half of the young, from the nursery school to university, go to Catholic schools; the Catholic hospitals represent more than half of the available beds and the catholic trade-union is the biggest in the country; it is also patent that the Catholic hierarchy has a certain influence on the laws elaboration, as for instance in the case of the law of abortion. In radical contrast to France, in Ireland, Italy, Spain and Portugal, there existed until very recently (essentially for the two first of them), a confusion between public and religious laws in private matters such as marriage and divorce. If nearly everywhere in Europe the links between the state and religion are now unofficial and if indeed the influence of religion on political matters is more and more tenuous, it remains the case that the populations still very often identify themselves as "Catholic" when they are Belgian, French, Italian. . . --- even if, as it is the case, they have only very slender links with the Church, often reduced to the "rites of passage" and to the Christmas eve celebration, everything goes on as if to be Italian, Belgian, Spanish, etc., was equivalent to being Catholic (and as if being Danish, Finn, etc., was to be a Lutheran).

In such circumstances, the question is clearly the one which Beyer asks: "How to re-orient a religious tradition towards the global whole and away from the particular culture with which that tradition identified itself in the past?"(Beyer, 1994:10). We will explore this question, considering especially the case of Roman Catholicism. Two reasons explain this choice. First Roman Catholicism --- as with other Christian Religions --- defines itself as a "world religion," which appears to offer it the possibility of playing a role in globalizing conditions. Secondly, we shall see that Roman Catholicism feels at ease on this level, much more than do Protestantism and Orthodoxy. Different circumstances explain why the Catholic Church intends to play a role on the stage of Europe and to take the opportunity of the unification of this part of the World to reappear on the public scene, from which it was expelled by the processes of functional differentiation and by secularization. Many facts testify to this project and the strategy which has been developed to realize it.

One of the first expressions of this policy appeared on the occasion of Gorbatchev's visit to the Vatican in 1989. Evoking the "common European home," founded on Christian values, Pope John-Paul affirmed that "Europe must learn to breathe with two lungs again --- that of the Occident, bearer of liberty but sick from its opulence and permissiveness, and that of the Orient, decomposed by decades of dictatorship but rich in its profound faith, a faith which, indeed, had largely contributed to liberating it and which must serve as an example to the secularized Occident and teach it "real values" again. Still more recently there was the "ceremony of consecration of European Institutions to Our Lady of Fatima," which took place in Brussels, 1st June 1992. One may also point to the September 1988 opening in Brussels, of the "Institut Robert Schuman" (IRS). This is a school of journalism intended for young, lay Europeans or those of European culture, who already possess a university diploma and who have a "certain Christian commitment." According to its present director, M. Bauer, this school has a dual objective: it is entirely structured on the European idea; and it wishes to "train Christians for the media, who are faithful to the Church and who will remain in solidarity with the Church and Pope in all respects." The idea of creating such a school came from Piet Derksen, a Dutch multi-millionaire, founder and general director of "Center Parks," these "tropical, aquatic, paradises" which have recently sprung up in Europe.

A few years ago, Derksen ceded his part of the business in order to place himself at the service of the Pope, suggesting to Him the inauguration of an evangelization project using modern techniques. This is the project "Lumen 2000," set in motion by the Foundation "Witnesses to the Love of God," of which Derksen is the founder and president. Even if the IRS has appeared lately to be distancing itself from Derksen, the initial project has, none the less, been maintained and the intention of educating journalists who are committed to the Church's service in Europe remains.

This list could be extended, enumerating various examples, all of which affirm the existence of Europe and remind us of its Christian culture. Nevertheless, it is particularly important to describe two kinds of specific events here : the edition of a map of the so-called "Christian Europe"; and, secondly, the recent large gatherings of European young people.

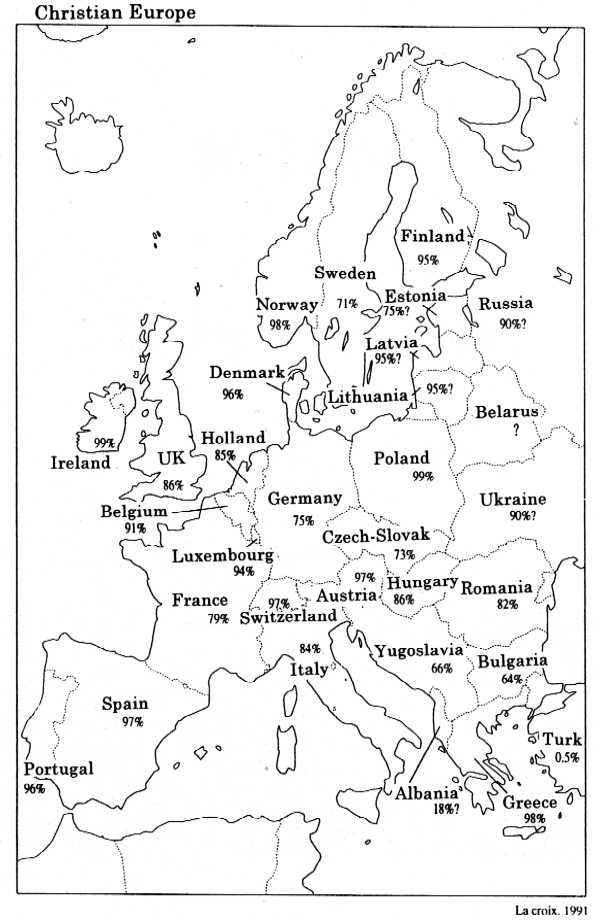

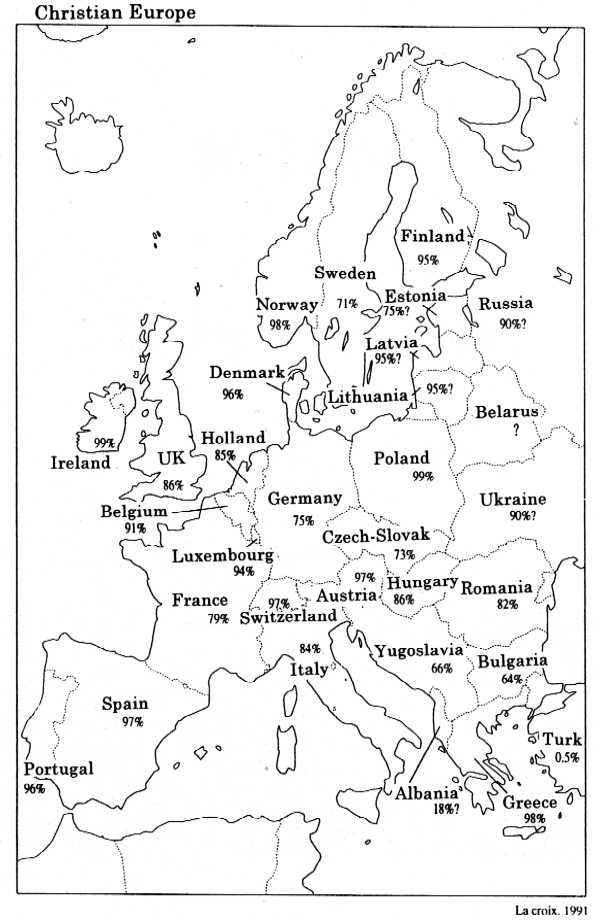

At the end of 1991 (from 28 November to 14 December), a Synod of European Bishops took place in Rome, specifically dedicated to Europe after the fall of communism. On this occasion, various newspapers published a map called "Christian Europe," showing the importance of Christianity on this continent. According to this document, at least 90% of the population of almost every European country are Christians (Catholic, Protestant, Anglican, Orthodox) and where there are fewer, Christians still represent at least two thirds of the population.

These figures can certainly be said to lend themselves to discussion, if for no other reason than because they gather together, under one and the same name, denominations which, even though issuing from one and the same "line," are far from always sharing the same ideas, even on religious matters. Besides, it is clear from the occasion when this map was published and from the Catholic character of the newspapers which published it, that this "Christian Europe" had to be understood as being "Roman Catholic." We will see, moreover, that other branches of Christianity have not the same view as the Vatican concerning Europe. In addition, these figures are open to criticism because they force the issue in taking as "Christians" people who in fact are so at best only nominally. The case of Belgium clearly illustrates this abuse. According to the map, this country is 91% Christian; yet according to the most recent data only 68% of the population state that they belong to a religion, 65% to Catholicism and 1% Protestantism. Furthermore, among the people identifying themselves as Catholics, only 15% (in 1993) practice regularly on Sundays, which does not mean weekly (Voyé and Dobbelaere, 1992:163). Even if a majority of Belgians continue to have recourse to Catholic rites of passage, the orthodoxy of their beliefs proves to be weak, just as is their respect for the Church's moral rules, particularly in the area of family morals (Voyé and Dobbelaere, 1992:202-222).

Thus, while it remains true to say that Belgium is a country that has been profoundly marked by Catholic culture, it is equally correct to affirm that the Church-institution has largely lost the clout it had (Voyé, 1988b). Today one may even observe that consciousness of the Catholic origin of its culture is becoming blurred. For example, fewer and fewer people know what Pentecost signifies. . .aside from the fact that it means a long weekend off. There are still fewer who remember at all the role the Catholic Church played in the very creation of Belgium as a country, in drawing up its constitution, in developing its school and hospital system. Perhaps above all, they forget its role in its "politics of compromise" which resulted in instituting in Belgium a unique mode of conflict management, in virtue of which it is often consulted by various countries needing to solve cultural, i.e. ethnic and religious problems analogous to those solved by Belgium without bloodshed and without thus far being torn apart. The memory of all this seems to be largely erased, and declarations of membership in the Catholic Church ought not to be assumed to imply strong religious conviction and still less to presuppose confessional allegiance and obedience to the institutional Church.

In Belgium --- just as in France (Hervieu-Léger, 1991) and elsewhere --- these declarations of membership are much more indicative of a certain cultural connivance inherited over the passage of time. For that matter, one may ask oneself what are the chances of the survival of that connivance once the references and "emblems" to which it clings, become more and more exhausted within the younger generations: in fact there are fewer and fewer parents who put their children in relatively regular and sustained contact with the Church, its practices and teaching; and it is well known that the family is a privileged vector of religious transmission, notably through the practices it inculcates.

One thing is obvious: the map of "Christian Europe" may be made the subject of much criticism, but as it happens, that does not matter. What is of interest for our purposes is that this map exists as such and that it is being propagated. What is important is that it exists before and after other manifestations, all, in our opinion, fitting into one and the same logic. For example, one need only think of the great gatherings of youths convened by John-Paul II. The latest took place in September 1995 in Loreto (Italy) which is an important pilgrimage place. Indeed, a cathedral was built there around the house where it is said, an angel announced to the Virgin Mary that she would become the mother of God. The story recounts how this house was rebuilt there with the stones that the Crusaders brought back with them from the Holy Land. This gathering was called "Eur-Hope for the youth" and the Pope insisted on the fact that Loreto and the Holy House were in a place which was exactly the centre of the European Continent, between West and East, i.e., between its two "lungs," as he likes to repeat. There the Pope told the thousands of young people who were present: "This is your house, the house of Christ and of the Virgin Mary, the house of God and of man," and he explicitly dedicated Europe to the Holy Virgin, which is a patent indication that when the Pope is speaking of "Christian" Europe, he has effectively in mind "Catholic" Europe, since it is evident that the Protestants may not recognize themselves in such a dedication.

During the week of the visit of the Pope to Loreto, many things were proposed to underline the close connection existing between the Catholic Church and Europe. First of all, people were reminded of the many illustrious European personages who had come to Loreto: among many others, Christopher Columbus, Montaigne, Cervantes, Descartes, Galileo Galilei, Montesquieu, Mozart and Brahms were mentioned, as well as a large number of kings and queens. As each of the many chapels within the Cathedral of Loreto is dedicated to an European Nation (England, France, Germany, Greece, Spain), the sanctuary was described as "a kind of sacred European mausoleum." This link between Loreto (and thus Catholicism) and Europe is confirmed, it was said, by the fact that in every European country, there exist chapels consecrated to the Virgin of Loreto, notably in the airport buildings (because She is considered as the protector of the people traveling by air).

During the most important evening meeting of the pilgrimage, the Pope clearly underlined the Christian character of Europe: "In this house," he said, "began the story of European life, culture and civilization. For if it is true that European civilization has different roots, it is also true that it first of all existed and grew from Christian root." Not only did the Pope insist on the important role that Christianity had played in the constitution of a specific European culture, but he also claimed the Christian origin of "these values proclaimed through this Continent for two thousands years: the values of freedom, equality and fraternity." And he encouraged the young to rediscover and to renovate this Continent in the spirit of Christianity "facing the oriental and the Islamic worlds."

Besides the repeated insistence on the Christian character of European culture, this last sentence is also of great interest. Indeed it defines Europe as different from --- perhaps even opposed to --- other parts of the world and, more specifically, to the Islamic and oriental worlds. The transfer of the Holy House from Palestine to Italy offers an opportunity to insist on that point. In the booklet published for the visit of the Pope to Loreto, this fact is expressly mentioned: "It is the encounter," it is said, "between Christianity born in the Orient of Palestine but which crossed the Mediterranean Sea with Greco-Roman culture, which constituted the heart of the Occident."

The evocation of this crossing of the sea (and the fact that the story claims that the stones of the Holy House were brought to Europe by the Crusaders who went to the Orient to take back the Holy Tomb from the Muslims) is certainly more than an insignificant anecdote. Effectively, although less explicitly, the old conflict between Europe and the Islamic world had already been evoked in another important gathering of European youth which took place in Santiago di Compostella (Spain) in 1989. On that occasion, the Pope delivered a memorable message: "The whole of Europe has again met around the memorial of Santiago as in those centuries during which Europe was being built, becoming an homogeneous and spiritually united continent . . . .The pilgrimage of Santiago constituted one of the strong points which encouraged the mutual understanding of the European peoples, as diverse as they are: Latin, German, Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, or Slovak. The pilgrimage brought them into closer contact and linked them with all peoples who, touched by the preaching of the witnesses of Christ, accepted the Gospel, and were born as peoples and nations"(Catholic Documentation, no.1841:1128-1130).

This message is clearly at the heart of the Pope's two main concerns: we should spare no effort in the attempt to "re-christianize a secularized Europe"; we should also try in this project to think about Europe "from the Atlantic ocean to the Ural mountains" for as the West helps the East to gain freedom, the East contributes to helping the West to believe again (Luneau et Ladrière,1989). This message also embodies another meaning. It takes on a quite particular connotation at this moment of European construction and at the very time when changes occurring in the East might modify the contours of Europe. It also takes on another particular significance, pronounced in the city of Galicia, where, in the face of the "infidel" menace, lie the remains of the patron Saint of the Reconquest at a moment when the revival of Islam troubles many.

Considering these different facts, proposed here as examples among others that are possible, two things are to be underlined. First of all, this Christian Europe is specifically a "Catholic" Europe and, secondly, the interlocutor is indeed the unified Europe and not the States who compose it.

We have already mentioned that what the Pope has in mind when he is speaking of a "Christian" Europe is in fact a "Catholic" Europe. How, indeed, might one imagine that the Protestants will recognize themselves under the banner of the Holy Virgin, proposed by the Pope! But there is more than that.

If, as we have seen, the Roman Catholic Church as such is very positively concerned about the construction of Europe, the same is not absolutely true for the other branches of Christianity. Certainly each of them says that it sees in a unified Europe a greater chance for peace and an opportunity to develop ecumenism (although fearing that in the perspective of the Catholic Church, ecumenism signifies a reunification under the authority of the Pope). But at the same time, these Churches develop an ambiguous feeling when they consider the connotations attached by the Catholic Church to its vision of Europe. Let us see some of their reservations related to this.

Since the beginning, the Protestants have had a relatively skeptical and distant attitude towards Europe. Three main concerns motivate this difference with the Catholic Church.

First of all, as Willaime indicates (1995:313), in Europe, historical Protestantism is intrinsically linked with the affirmation of national and regional identities: the Presbyterian Church of Scotland, the Protestant Church of Würtemberg in Germany, the Reformed Church of the Vaux region in Switzerland. . .are examples of the close relation between a particularistic affirmation and a specific Protestant denomination. This is conforted and reinforced by the fact that there exists no one central and hierarchical authority in Protestantism as there is in Roman Catholicism. The politics of the latter was always to eliminate the tendencies of national or regional religious specificities, as for instance the Gallicanism in France (Voyé,1988a) and we see that for some years the Vatican has objected to the claims, in reference to the principle of subsidiarity, of some bishops conferences, for more power, in particular to be able to realize a better "inculturation" of the Catholic Church in a particular context (Voyé, 1988a). These differences between the Catholic Church and the Protestant Churches are certainly an element in explaining the "reticence" of the latter and, on the contrary, the support coming from the Catholic Church toward the unification of Europe.

The reservations of the Protestant Churches are all the more pronounced because economical and political Europe in its first stage is essentially a "Catholic" Europe. At the origin of the project were catholic social-democratic figures (the Italian de Gasperi, the French Schuman, the German Adenauer) and among the twelve first countries involved were seven quasi-exclusively Catholic ones (Belgium, France, Ireland, Italy, Luxemburg, Portugal, Spain) while two others were mixed (Germany and the Netherlands). So whereas Catholicism represents 60% of the population in this Europe, Protestantism concerns only 16%. This quantitative domination easily induced the image of a Vatican Europe." And before the fall of communism, the Protestant objections to it were all the more pronounced because this Europe under construction seemed to some of them to be a kind of resurgence of the Roman Empire, intending to serve the capitalistic and geo-political interests of the West.

Last but not least, Protestants appear to disagree with the Pope's proposal to "re-christianize secularized Europe" as it has been explicitly stated. The documents published after the European Protestant Assembly which took place in Budapest in 1993 clearly show a significant difference on this point. Indeed, as is underlined by Willaime (1995:320), the Reformation insisted on "evangelical freedom" and Protestantism explicitly recognizes the beneficial consequences of secularization, which it is said, was influenced by Protestantism. For this religion, the differentiation between State and Church is seen as valuable, and the church recognize that the Enlightenment permitted the manifestation of essential values found in the Gospel. Besides this, it is pointed out that Christianity is only one of the different strands that are concerned in the construction of Europe: Islam and Judaism in particular also have a history that is partly rooted in some European Countries. This insistence on the pluralism of the religious and philosophical heritage of Europe differs dramatically from the view of the Roman Catholic Church which defines Europe as a Christian Continent, and in its mind, as a Catholic Continent, since other Christian religions are seen as dissentient and are expected to return to the Roman Church.

As with the Protestant Churches, the Orthodox Church is also more or less reluctant to see Europe going, as the Pope puts it, "from the Atlantic Ocean to the Ural Mountains" because the Orthodox Church considers this Europe as being essentially managed by Catholic and Protestant countries, according to a liberal and materialist model. Besides this, the leaders of the Orthodox Church do not very much appreciate that, since the fall of the Berlin wall, Catholic priests and Protestant ministers have gone to Eastern Europe with a kind of missionary project. This is all the better so that the Orthodox Church considers itself as invested with the moral duty to entertain and protect the specific "Russian soul" and to control the functioning of the new so-called democratic governments to avoid the materialist drift experienced by the West.

A problem of the same kind appears in the Anglican Church: the deep connection of this Church and the State provokes the fear that, with the efflux of time, Europe will reduce the specific identity of the country and the legitimacy of this particular Church.

The European field is thus free for the strategy of the Catholic Church which, as we have seen, clearly occupies it. It is all the more likely that the European authorities appear to regard positively the Church's repeated affirmations of the Christian Character of Europe. Different facts testify to the sympathy which they manifest to this assertion. Naturally we have to take into account that the Pope is also a head of State, which is not the case of other religious leaders. Let us simply recall the different official visits of the Pope to the European Parliament and to the different seats of European authority, in Brussels, Luxemburg and Strasbourg. Naturally we have to take into account that the Pope is also a head of State, which is not the case of other religious leaders. Let us also mention that the main ceremonies of the youth gathering in Loreto were transmitted on Eurovision and by the network "Europe by satellite" freely put at the disposal of the organizers by the European Commission. And last but not least, in March 1992, Jacques Delors, the President of the European Commission, met with the members of the "Commission of the Bishop's Conferences of the European Community" (COMECE) and spoke of this concerns for Europe "to have a soul and "to be given a meaning." And the Church, he said, is among "les instances de sens" (Hornsby-Smith,1995).

It is nevertheless important not to misunderstand this acceptance of Catholicism as the cultural background of Europe. First of all, the European Community began as an economic unit and is still essentially perceived as an entity motivated by a project of internal economic regulation, designed to establish Europe as a serious partner in the context of the economical globalization. So defined, Europe is confronted with serious difficulties when it attempts to develop a European consciousness among the populations of the different constituent countries. Not all these countries have the same measure of conviction regarding their participation within a unified Europe --- some of them in fear at a high level of losing prerogatives such as the control of their borders, and the emission of their own money. And the people, who for ten to fifteen years have experienced serious economical crisis, are tempted do attribute responsibility for such problems to Europe and the rules of exchange which are being imposed.

In the face of this skepticism and this reluctance, the Catholic Church appears to offer new perspectives, capable of solving these difficulties. First, it seems likely that while maintaining pastoral and diplomatic relations with the different states of Europe, it is not the states as such which the Catholic Church regards as valuable interlocutors. Inside the Europe that is being constructed, the interlocutors are essentially not the states but the "nations" of which they are composed and which are sometimes settled across state borders. For various reasons, the Church undoubtedly feels more at ease on this geo-political level.

First, in some way the modern state doubtlessly retains a memory of itself as the child of the Enlightenment with its anti-religious rationalism. The state is the actor which has substituted itself for the earlier structures within which the Church occupied a privileged place: family, guild, and the local community. The simple idea of Europe may, on the contrary, remind the Church of the time of its glory: the Christian Middle Ages which, no matter to what extent it might be shrouded in myth, is in some way its "golden age."

Furthermore, the model of the Church's hierarchic structure is certainly better suited to Europe than it is to states. In fact, this structure recognizes only two principal authorities: the pope and the bishop. This indeed, is the reason that Rome is opposed to any attribution of official recognition whatsoever to the National Bishop's Conferences, which it suspects from the outset of bringing forward the risks of Gallicanism (Voyé,1992). With Europe, and the regions to which Europe may be able to give preference to the detriment of states, the Catholic Church may perhaps be able to rediscover two places of anchorage more in correspondence with its own structure: that of its international and supernational dimension, of which Roman power is the emblem; and that of its regional organization with the local bishop. Just as in earlier, immobile societies the parish was the locate around which the structure of daily life was organized, the region-diocese may become the decisive level of pastoral organization for a society which lives on a larger scale, thanks to expanded possibilities of mobility and the positive evaluation of this mobility.

Finally, one should not neglect the fact that the Catholic Church is an organization whose hierarchy is capable of working out strategies (Remy, 1992). In this sense, one can reckon that it is no stranger to the globalization process which is at present reorganizing the economy and the polity on the basis of vast "world-regions." Europe is one of these. In fact, it is on this scale that the stakes must be defined, the solutions found, and the decisions taken. Therefore, the Church, too, must position itself on this level if it wants to demonstrate its existence and express its point of view on the public scene. For that matter, the Church has that much more reason to assert itself on this level in that, whatever the image of the Europe of tomorrow might be, many expectations are being invested in this Europe. In this respect, the European Values Study (1990) has shown that in all countries of the Europe of the Twelve (except in Great Britain where it is practically even) confidence in Europe is far greater than in the respective national parliaments (taking European countries as a whole, "a great deal," respectively 12% and 6%; "quite a lot" respectively 45% and 37%). Henceforth, Europe appears to be a sort of "myth for tomorrow", sometimes rediscovering moreover the myth of origins, as some would have it, in rewriting history and as the Catholic Church, in the person of the Pope, has proposed on various occasions (Luneau and Ladrière,1989).

We still have to ask ourselves: on what grounds then and in what form does the Church intend to assert itself; what sort of role is left to it on the public scene so reorganized?

After having long played a direct political role in many Western European countries, the Catholic Church has been practically reduced to silence on the public scene. If it wants to reappear there and to play a role at the new pertinent political level --- which, as we have seen, is Europe --- the Church has to be recognized as --- to put it in the terms of Luhmann --- (1990) a resource for other systems. "The Church must provide a service that not only supports and enhances the religious faith of its adherents, but also can impose itself by having far-reaching implications outside the strictly religious realm" (Beyer, 1994:78).

What, then can be the "performance" of the Catholic Church, i.e. its capacity, for application to problems generated in other systems but not solved there. According to Beyer, there exist two possibilities for religion to enter the public (essentially political) arena: an ecumenical one, which supposes that religion looks at the whole as a whole; a particularistic one which implies that "religion champions the cultural distinctiveness of one region through a re-appropriation of traditional religious antagonist categories" (Beyer,1994:93). Let us see what in Europe is the double strategy of the Catholic Church confronted with this exigency.

As we have already said, if the fathers of the European idea had first of all in mind the preoccupations of peace after the two dramatic wars which had vigorously shaken it, very quickly the process of constructing Europe focused on an economical perspective. Such a purpose, however, is not very readily able to mobilize citizens, most of all if it is practically developed in an economically troubled period as the one existing now in Europe.

Consciously or not, it is clearly evident that the Catholic Church proposes an alternative image of Europe and offers its services to design it. This image is of a Europe of human rights, the Catholic Church presenting itself as "an expert in humanity," able to help in fulfilling this aim. In the following pages, we provide a few examples to illustrate the sense of this role that the Church is attributing to itself. Let us make it clear that we shall not give priority to the Pope's discourses ; not, certainly, because they are not important, but rather because we prefer to show how they (analyzed for example in "The Dream of Compostella") are to be found again in the mouths or acts of other prominent personalities of the Church in Europe, confirming the existence of the project that we feel we see taking shape.

Speaking at the (Belgian) Royal Institute of International Relations the 14 of January 1987, Cardinal Danneels (1991:5) defined in three points, as follows, the role of the Church within the international order: the Church points to the attention that must necessarily be paid to the dignity of man and to his rights ("the Pope comes back to this each time he addresses the Diplomatic Corps"); "the Church must also denounce the fact that human rights are denied in the world"; it must also "help take advantage on the practical level from mutations and changes in order to move towards an increasingly happier world." And the Cardinal went on in saying that it was not the Church's task to sketch out the concrete paths, but that "the Catholic church considers itself charged with a mission and capable of breathing its moral and religious tenor into a world in need of it. . . It needs it because of the evil to be found to some extent everywhere. . ." And Danneels went on, "I take evil here not in the Christian sense of sin, but in the sense of an evil which destroys man." It is because of this "conspiracy of evil of this planetary and mondial alliance of evil" --- Danneels went on --- "that in some of its documents the Church speaks of a moral authority which, liberally accepted by all the peoples, by all the States of the world, would be sufficiently strong and able to ameliorate, promote and increase man's happiness. Will humanity be one day capable of freely consenting to such an authority? I don't know. As a Christian, I would say that the sole authority capable of doing it is God and a little bit --- insofar as it remains faithful to God the Church."

This discourse, pronounced by one of the most influential Cardinals and one closest to the Pope, is of great interest. In our opinion it clarifies the role that the Church intends to perform on the public scene in Europe. Four elements seem particularly noteworthy of attention.

First, when one studies this discourse, the Church is placing itself in the role of a "third-party." As opposed to earlier situations where it was more or less officially linked to certain political regimes and certain states, it defines its role as being situated on the international level (one might certainly say that this discourse was one for a given occasion, but the theme returns again and again). It is even more exact to say that the Church is placing itself above and beyond all states. This exteriority thus permits it to present itself as being beyond all conflicts and thus as neutral and more competent to evaluate and counsel.

Subsequently, it may be observed that the Church sees its mission as "help(ing) on the practical level in reaping the advantages from mutations and changes in order to move towards an increasingly happier world." One cannot help being interested in such talk, which proposes that the Church's mission is to help in developing happiness in the world and not first of all in the great beyond. This project's immanent dimension is relatively new and, as such, undoubtedly reveals that the Church is increasingly anxious that its values should correspond with those which Europeans espouse, as revealed by the European Values Studies.

Furthermore, it is striking to note that this discourse is intended to be valid for all, Christians and non-Christians alike. Thus, when evil is spoken of here it is clearly pointed out that limiting it to "sin" as defined by the Church is out of the question: it is evil in general that is at issue here, the evil that "destroys man," and which elsewhere is defined in this talk: undefinable anxiety; mistrust of others; pessimism; skepticism; fatalism; structures leading to autonomous lives; the destruction and chaos which menace humanity if natural resources continue to be depleted; the arms race; and the misery of some coupled with unbridled consumption on the part of others.

All of this evil must be confronted by "human rights." It is particularly interesting to note this third point. In effect, the Church does not intend so to dominate evil by making appeal to its own doctrine, to the Gospel, but indeed rather to human rights! On this subject, Luneau and Ladrière (1989:172-178) make an important threefold remark. Observing that the Pope also often makes reference to human rights, they point out that it is to the Universal Declaration of 1948 to which he makes appeal and not to the 1789 Declaration, to which the Catholic hierarchy was violently opposed at the time. Luneau and Ladrière state moreover that the hierarchy condemned believers who participated in the drafting of the 1789 Declaration, which was associated with the French Revolution and the secular Republic. Elsewhere, these authors agree with us that the Church today is placing itself on the side of the civil society and against the depreciated state. They say that today "human rights cease to be the critical reference to positive law within the state or states and tend rather to be the individual's recourse against the state. On the one side are to be found the individual, the civil society, and the nation, and they have human rights `going for them.' On the other side is to be found the dangerous reality of the state."

Finally, Luneau and Ladrière note that the Pope "catholicizes and de-secularizes" human rights: as if "human rights were nothing other than the expression of the dignity of the human person (a message pronounced in Germany in November 1980 and in Poland in July 1987 . . .). Kantian philosophy, to which on this point modern society is heir, based the dignity of the person on his autonomy, that is on his capacity to provide himself with his own laws, as imperatively and objectively imposed upon his will, through reason, while reason itself was systematically submitted to critique. The dignity which the Pope talks about is foreign to this conception of autonomy. It seeks to found itself upon the biblical idea of man in the image of God (a message pronounced in Austria in September 1983)." To this shift of meaning which the Pope brings about, Luneau and Ladrière consider must still be added the fact that the Pope diverts the origin of human dignity when he says "who can forget that consciousness of human dignity and the corresponding rights --- even if one does not employ this word --- was born in Europe, under the influence of Christianity (a message pronounced before the European Court of Human Rights, December 1983)." And we have seen that in Loreto (1995) the Pope still insisted on the relation between the principles of "Liberty, Equality, Brotherhood" and Christianity.

Defining itself as a "third-party," and assigning itself the mission of aiding in the attainment of happiness in this world for all men, whether they be Christian or not, the Church --- in the words of Danneels --- specifies that its role is to be situated "neither in politics nor in economy," and that "it is not up to it to determine the means of action in a concrete manner." It asserts itself as a moral authority of reference. Its ascendancy is not based on constraint, but on respectability. The Church is not in the first place dependent on disciplinary force, but on a legitimacy which it claims is granted to it, and which in fact is hardly contested, except perhaps by a portion of those who declare themselves most involved in the Christian project and who professionally or otherwise invest the most in institutions bearing the Christian (Catholic) label.

Let us make this point quite clear. To say that the Church is trying to assert itself as a moral authority rather than as a disciplinary authority in no way signifies that it renounces its second role. Quite the contrary, as testified to, for example, by recent "instructions": to Catholic universities, and on the vocation of theologians (1990), or further, those concerning censure and re-establishment of the "nihil obstat" (1992). But the Church knows that this disciplinary role concerns only a small minority of people, the majority not even being conscious of the existence of such "instructions." The "media-oriented" accent is placed much more on the Church's moral role, a role moreover presented as being disengaged from any particular denominational ties. In effect, it is a question of touching the masses on the symbolic level by taking advantage of the atmosphere of doubt and uncertitude that "advanced modernity" (post-modernity) is experiencing. This atmosphere is notably linked to "the end of great narratives," to refer to Lyotard (1979). Indeed, the collapse of the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe and the failure of the Welfare State in Western Europe seem more and more to witness that socialism has, until now, been an unrealistic project. On its side, science is less and less considered capable of solving all man's problems and today its "nefarious effects" are ceaselessly brought to light. If rationality, the key project of modernity, is not abandoned, none the less, it unceasingly witnesses its own incapacity to meet all human expectations.

As to the individual, promoted as the centre of meaning by this same modernity, he increasingly seeks new "lieux" of solidarity as well as innovative modes of reconstructing of social ties. Thus, without purely and simply vacating modernity's contributions, the radical and hence incomplete character of modernity is brought to light today. The disarray which this provokes opens up a space for intervention for the Church. Here, it can present itself as the bearer of a prophetic role and as the guardian of values offering an escape from the uncertitudes and contradictions of the modern world. And it is not without interest to note that this proposal is often welcomed outside the Church itself. We have already seen that the platform of political Europe were at different times opened to the Pope. And in various circles, not especially connected with the Catholic Church, there exists a latent and sometimes explicit expectation that "a moral authority" expresses another view of Europe from that of the market. For instance, certain sociologists, atheists for that matter, went so far as to call upon religious actors in order to redefine a world in which "all the references are mixed up." Thus Balandier disignated the priest-prophet as one of the "figures of recourse over against the subsidence of meaning. . ." He says that "this sort of figure always emerges in times of uncertitude, when everything is upset and new configurations remain indecisive" (1985:200).

As a moral and prophetic authority, the Church thus appears to want to speak with a "de-clericalized" voice, thereby enabling it to be heard far beyond its own walls. Yet, the Church may be more or less consciously waiting for the legitimacy that may be attributed to it on this level to contribute to the reaffirmation of its internal power: how can those claiming to be faithful to a Church the pertinence of whose word is recognized well beyond its jurisdiction want to back out of the rules it defines for those claiming to belong to it?

Thus, for public opinion, the accent seems to be placed on the Church's general moral role and on its prophetic capacity. But without denying its existing solicitude for exercising this role, the Church makes at the same time a detour which facilitates the re-establishment of its internal disciplinary power, perhaps even of a new form for "Christendom." Is this not, for example, the best way of understanding the Roman recognition of "Opus Dei" as well as "Communione e Liberazione," two movements which, beyond their strictly religious aspects, aim to control the general functioning of society, taking particularly the economic and media sectors as their starting points (K. Dobbelaere, 1991)? Opus Dei, which was declared "personal prelature" in 1982 and whose founder Escriva de Balaguer has just been beatified, clearly affirms its project of restoring traditional Christian values and the old orthodoxy. In this way it places itself at the service, including financial service, of Rome, by infiltrating first and foremost the media sector, higher education, and the service sector, particularly banks (Walsh, 1989). As for Communione e Liberazione, it is a mass movement which develops a social, economic and political project seeking to offer an alternative to capitalism which is considered to be sapping Christian culture (Abbruzzese, 1989). Certainly, these two movements do not limit their activities to Europe, but it is clear that they find there a privileged field of action, underpinned as much by the evocation of the "Christian Europe of the Middle Ages" as by the denunciation of lost values, stolen as they were by the materialism common to both liberalism and Marxism.

Thus, at the same time and with various accents in relation with different of its main actors, the Catholic Church seems to have two goals. First, it is searching to legitimate itself by playing the role of a unique moral authority for Europe, and thus hoping to perform a necessary but hitherto missing function in the construction of this world-region. And secondly, through some of its branches, especially well-considered by the Pope, the Catholic Church tries to re-establish a holistic Europe, where it not only controls the spiritual domain but where also it would influence other systems, in particular political and economical systems.

If the Catholic Church is trying to play a significant role at the global level of Europe, it also reaffirms its pertinence inside this world region.

Among the different problems related to European construction, one must refer to the question of defining the internal components of Europe which are to be taken into account. Different views exist on this point: some insist that the states are the evident elements of Europe (this is for instance the case of France) while others take the opportunity to reaffirm the importance of nations and regions. The debate is significant: it places in opposition to each other the supporters of the primacy of political and administrative structures, to those who emphasize the cultural, usually linguistical and emotional communities which exist within the same state and which may extend across the borders of other states. Indeed, it appears to be only by progressive shifts in meaning that one comes to speak of the "Nation-State" so that the differences between a cultural community and a political organization have gradually been disappearing.

According to Habermas (1991), the idea of the state corresponds to a specific moment in history and this moment is in process of being overtaken. In this author's opinion, when in acquired its full character at the end of the 18th century, "the state secured the overall conditions under which capitalism was able to develop world-wide. It provided both the infrastructure and the legal frame (work) for free individual and collective action"(1991:3). In this sense, the state did not correspond to a permanent necessity: it may be above all an organizational authority serving a specific phase in the development of capitalism. The nationalist movements which are convulsing various western (and other) states today may thus reveal the artificial character of the assimilation between "state" and "nation" and of the concept of "nation-state." And re-emergence of the idea of "nation" disconnected from that of "state" is all the more pronounced since most European states find themselves challenged in different ways: the financial compromissions of leaders of various major political parties; the question mark over the social security systems; the powerlessness of states to resolve different types of problems which arise today, such as those of the environment, AIDS and drugs and others which, as Touraine emphasizes (1990), are related to the rediscovery of the subject, both in itself and in its concrete categories of sex, ethnicity and territoriality. Thus the great issues are displaced and become those of education and health, those of communication and those of human rights. Bauman (1990:433-435) adds that it is impossible to meet the challenge posed by these new stakes through the establishment of authoritarian and formal rules making claims to generality: a rule can only result from taking actors into account in concrete "communities" where they live with their emotions and affections. Faced with these new places of emerging meaning, the state finds itself largely disqualified, this state being founded in order to assure an exclusive and global order and to reconstruct an at least apparent, general consensus, based upon a proposition of neutrality, rationality and equality, after having upset the traditional structures of power and integration: family and trade (guild), local community and religion.

This disqualification of the state is not, as we have already seen, displeasing to the Catholic Church which remains worried by the original anti-religious rationalism of the state and is still anxious about the risk of a resurgence of Gallicanism. Therefore we can understand that, beside its investment on Europe, the Catholic Church may consider the re-affirmation of particularistic belonging as an opportunity to re-activate the links it has traditionally had with these entities. This is all the more important for its strategy, since if its policy at the global level of Europe is essentially oriented to the people in power, what is important at the particularistic levels is to meet with large numbers of people "at the grass-roots." And it is of course generally the "ordinary people in their everyday life" who are concerned with the various opportunities which the Catholic Church facilitates for the expression of their particularistic identity. Indeed, in regard to the emotional dimension, these people may find in the diverse forms of "popular religion" many opportunities for the expression to their feelings.

Since we have used the term of "popular religion," we need to clarify what we intend by it. It would be a mistake to consider popular religion to be the concern of only the lower strata, characterized by more or less naivety and by simple mindedness. The results of research make it apparent that neither social class, nor educational level are discriminant in this field. If popular religion may sometimes take various forms according to these variables, it is evident that people in each social "milieu" are turning to some kind of popular religion, particularly at certain times and in relation with problems we will identify later. The specificity of popular religion is thus not to be sought in its particular type of public. It rests rather on concrete gestures and lies in the fact that it involves the various senses. It is probably this character which explains why popular religion is sometimes rejected, in the name of a "deep faith" and of positivist rationalist thought. Nevertheless, recent works of anthropology and sociology emphasize that the sense is imprinted in the body and that corporal practices are in themselves a very important language. Such concrete practices as pilgrimages, requests for blessings, and offering to saints have to be considered more seriously than what is offered by summary rationalist evaluations.

Among the various significations which these kinds of practices may take on, some are particularly interesting for our present purposes. Indeed the practices of popular religion, which are highly polysemous, often appear to express a specific identity, most notably, a territorial identity. This is essentially the case for the cult of saints and for pilgrimages: every parish but also every region is dedicated to a particular saint and traditionally, people have every year a celebration for their protector and pilgrimages are organized to a place that was significant in his life.

Very often these practices become ambivalent: they mix some religious feeling with a political nationalistic affirmation, particularly when a problem exists concerning the recognition of a particular cultural identity. This is for instance the case with the highly increasing pilgrimage to Knock: lost in the midst of the peat-bogs of the West of the West of Southern Ireland, this place it is said the Holy Virgin appeared in 1879, each year gathers many hundreds of thousands of pilgrims, who go there to express their faith but also explicitly to support a political claim for reunification of Ireland. And Czestochowa, with its Black Virgin was and still is the symbol of the independence of the Polish people; it was under the protection of this Virgin that Walesa placed the action of "Solidarnose" against the political power guided by Moscow and for the recovery of the freedom and sovereignty of Poland. Fatima in Portugal offers another example of the emotional-political signification of a sacred place: it is the place where Portuguese emigrants normally go when returning for holidays to their country; they undertake this pilgrimage, as shown by research (Lopes, 1986), to reaffirm their belonging to the Portuguese nation and as a liminal rite between the country where they are working and presently living and the one in which they have their roots. It is also notable that in the cities of Northern Europe where an important amount of Portuguese emigrants live, chapels in honor of the Virgin of Fatima have been created, which are the regular gathering places of these people who feel a need to keep a link with their fatherland. In a more ordinary sense, the internationally well known Lourdes, in France, is a gathering place for the people of Bigorre, a South-Western region of this country, while to reaffirm their specific identity the inhabitants of the Liège region, in Belgium, go every year on pilgrimage of Chevremont, an old abbey on a hill which was a significant point in the defense of the region against nazism.

There are many examples of the same kind. All of them express the importance of such "totemic" places, as Durkheim would put it (Durkheim, 1960:142-239) i.e. places where "regular collective expressions of social sentiments may take place in a ritual form", these expressions being considered as essential for the maintenance of solidarity and identity of a "clan," what is to say that they are indispensable for the permanence and survival of it. And in these places, the honored Virgin or Saint plays the role of this "some more or less concrete object" --- as says Durkheim, "which can act as the representative of the group."

In Europe, Catholicism offers many such places and "objects," which among other significations, are invested with a local or a regional identity. It is also apparent that over the last few years, there has been a significant increase in the popularity of such places and objects. This upsurge appears to be parallel to the development of the European Community, on the one hand, and to the collapse of the credibility and the efficiency of the state, on the other hand. Indeed, if Europe gives rise to some hope, the positive consequences of its unification are until now not directly experienced as an improvement of their lot by the people: often, the Community appears to be a bureaucratic organization, which makes decisions remoted from everyday life and its particular situations and problems.

We have already underlined that the state is less and less able to control the economy (and so, particularly, employment and unemployment) and to meet the targets that were met by the Welfare State. Confronted with these two elusive institutions, many people try to (re)discover some significant "we," where the individuals many affirm and defend their personal freedom in its specificity. We are here confronted with an apparent paradox: the recognition of the personal freedom of the individual is the result of Modernity, "inspired" by the Enlightenment, while the reaffirmation of group identity as "we" seems to be a return to pre-Modern times and precisely to the concrete categories (ethnicity, territoriality) that Modernity intended to eradicate. A world of reason and progress was indeed supposed to destroy ascription and mechanical solidarities. But in so defining its purpose, modernity progressively considered the individual as a monistic citizen, the equivalent to another. This indifferentiated citizen was also supposed to be subordinated to the system, designed as "a rational social body" in which economic development, political democracy and individual happiness were supposed to be closely linked. It is against or nearby this abstract view and most of all against or nearby the unsatisfactory and perverse effects of its implementation that today different forms of particularism are reappearing.

But there is more: if popular religion may be used as a means to reaffirm national and regional identities, it also offers answers to problems which are not encountered by any specialized functional system. As Beyer says, "Because the differentiated functional systems concentrate on specialized means of communication and not on the total lives of the people that carry them, they leave a great deal of social communication undetermined, if not unaffected. From the casual conversation with the neighbour across the fence to the voluntary organization, from social networks to social movements, there is much that escapes these nevertheless dominant systems" (Beyer, 1994:56). And precisely in these fields, popular religion --- which is most specific to Catholicism --- offers many spiritual but also economical supports. We have demonstrated, for instance, that pilgrimages are privileged places and moments in which to express a demand concerning the health of oneself or of family members and friends; people go also to these high places to ask for protection for their love affairs or to pray to avoid accidents, to find a job or to solve a financial problem. The expectation is not primarily to obtain the practical object of the quest but to find the strength to confront and to surmount these various difficulties or to come to terms with the fact that they may not be solved in the ways anticipated.

It seems to us that it is in this double sense --- a quest of identity and a demand to be able to confront difficulties in everyday life --- that the upsurge of different manifestations of popular religion are to be understood. Pilgrimages spaces and cults of saints --- whatever may be their specific religions significance --- appear to be instrumentalized in order to express particular identities and solidarities in front of the universalistic project of modernity and to find comfort in the personal and problematic circumstances of everyday life. Their success in these things is all the greater because they rest on concrete hieratic gestures which are considered as the best vectors to find and to convey solidarity, identity and distinctiveness and to express emotion and affectivity.

The globalization which is currently actually in process is clearly not only a political and economical affair. It concerns every aspect of life, as Robertson underlines it, on the levels of "national societies," individuals or selves, relationships between national societies or the world system of societies and humankind (Robertson, 1992:25). And even if "millions of people remain relatively unaffected by this circumstance, they are certainly linked with the world economy" (Robertson, 1992:183) and, we would add, with the world culture, at least through TV and entertainment programs.

The question we just discussed was to explore whether religion played a role in this process and if so, what kind of role it plays, especially in Europe, considered as a "world-region" in emergence. Through our exploration of this subject, it first of all appeared that it is the Catholic Church which seems to be the most concerned by European construction.

In a context of functional differentiation, where Catholicism may no longer expect to be "the sacred Canopy" which it once was in Europe, the only possibility for this religion is to recognize that it is one of the differentiated functional systems. The question then is not only the one which was pointed out by Beyer, namely to see how religion, considered as subsystem, relates to the society as a whole (from this point of view, its function refers to "pure" religious components such as cure of souls, search of salvation, etc.), but also to see how it relates to other social subsystems in order to establish its importance for the profane aspects of life (Beyer, 1994:79). This last question refers to what Luhmann (1992) calls "performance," i.e., the usefulness and the use of religion in confronting problems generated in other systems but not solved there or simply not elsewhere addressed.

In our lecture, we have tried to show that Catholicism is exploring performance in two ways. The first is mostly oriented to leadership in Europe. It is explicitly a proposal to consider Catholicism as intrinsically linked with the culture and the values of Europe and so to give meaning and "a soul" to the project of unification of this Continent. This project, inspired by the necessity for Europe to define itself on the battle-field of the world economy, is until now essentially economically oriented and, as such, encounters many difficulties in the opinion of people. This affirmation of the Catholic character of Europe is clearly intended to incorporate the entire population living on this Continent: denying the fact that Europe is becoming increasingly culturally and thus religiously, heterogeneous, the Catholic Church does not speak at this level in terms of its specific doctrine and rules but more generally in terms of "human rights." On the other hand, at different moments, the Church, through the voice of the Pope, speaks about the identity of Europe in the face of other parts of the world and especially in relation to the Islamic world. This particular insistence is very significant: there exists a long tradition of enmity between Europe and this part of the world (let us remember the Crusades).

This tradition seems sometimes to be reactivated in the declarations of some Muslin leaders, who speak of the "sacred war"; and the fact that many migrants to Europe come from Islamic countries constitutes a favorable ground for the development of racist feelings, most of all among European workers who, erroneously, consider that these foreigners take their jobs and take advantage of a social security system essentially paid for by natives. In this atmosphere, every affirmation of a specific European identity and values system is particularly welcomed. So when the Catholic Church proposes to consider Europe as deep-rooted in this religion, it is not surprising that it is favorably heard, both by the political leaders of Europe who are looking for something additional to an economic legitimation of the unification of this part of the world, and by large sections of the public who, becoming more and more anxious in the face of an increasing unemployment, rising everyday violence and insecurity and growing social inequalities try to see their specific identity reaffirmed and, sometimes, seek to identify "the other" in order to strengthen its own self consciousness by pointing out a scapegoat.

Besides this aspect, Catholicism seems to play another performative role, essentially this time for the people. Through the practices of popular religion, it offers places, personages and objects to give concrete expression to nations and regions which re-emerge from the deceasing legitimation of the states systems and their incapacity to solve the various problems we have mentioned. Through the same kinds of practices, Catholicism also helps individuals and voluntary networks flourish in civil society and to express the feelings, needs and hopes that any functional system seems to be capable to take into account.

Thus if we consider the various world images, i.e., "conceptions of how the intramundane world is actually and/or should be structured," defined by Robertson (1992:75), we would certainly agree with that the Catholic Church develops a "gemeinschaftliche" image. It is clearly in its tradition but the scale of which it now takes account is much larger than it was before, when the local parish was the fundamental level of its pastoral work and of its power. And we would certainly also join Robertson when he considers that this image refers mainly to individuals. But we would hesitate to follow him when he says that the Catholic Church understands this "Gemeinschaft" in terms of "a fully globewide community" (Robertson, 1992:75), which it considers as the only possibility to construct a global order. From our point of view, the Catholic Church --- at least in the mind of the Pope --- is here very ambiguous. On one side, it is certainly true that, defined as a universal religion, Catholicism would like to realize this globewide community --- and the various travels of the Pope testify to this hope. And it is also correct to say that it is the centralized version of this global Gemeinschaft which prevails in Rome: the latent conflicts with the bishops Conferences of Africa, Asia and Latin America who ask for more autonomy and an enlargement of "enculturation" possibilities notably illustrate the tensions which exist between a decentralized vision of Catholicism and the Roman purposes. But on the other side, as we have seen, Europe is still considered by the Vatican as the cradle of Christianity, a cradle which has to be protected against the influences of other cultures and religions and which, if necessary, has to live as a "a relatively closed societal community" (Robertson, 1992:75), alongside other closed societal communities, considered as less important that European (thus, in terms of Robertson, in an asymmetrical version).

Thus we suggest considering that the ultimate intention of the Catholic Church is certainly to realize "a fully globewide community" following the Roman rule in doctrine and ethics and the European cultural laws. But this Church has also a position of strategic withdrawal: if this goal appears to be unrealistic, then Europe will be the privileged territory for the display of Catholicism, alongside to other territories dominated by other religions and cultures.

ABBRUZZESE, S.,1989.Commmunione e Liberazione: identité catholique et disqualification du monde, Ed. du Cerf, Paris.

BALANDIER, G., 1985. Le détour: pouvoir et modernité, ed., FAYARD, Paris.

BAUMAN, Z., 1990. "Philosophical Affinities of Postmodern Sociology," The Sociological Review, vol. 38, no 3, pp.411-444.

BEYER P., 1994. Religion and globalization, Sage, London.

DANNEELS, G. (Cardinal), 1991. "Le rôle de l'Eglise dans l'ordre international," Studia Diplomatica, vol. XLIV, 1, pp. 3-15.

DOBBELAERE, K., 1991. "Binnenkerkelijke Nieuwe Religieuze Bewegingen: Een sociologische verkenning van moderne religieuze oriëntaties," Visie en Volharding, MCKS, Driebergen, pp.71-84.

DURKHEIM, E., 1969. Les formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse, PUF, Paris.

HABERMAS, J., 1991. "Citizenship and National Identity," A lecture during the conference "Identity and Differences in the Democratic Europe," Bruxelles.

HERVIEU-LEGER, D., 1991. "Dislocation des systèmes religieux-culturels intégrés et assimilation de la religion dans la culture," Revue Suisse de Sociologie, 17/3, pp. 538-543.

HORNSBY-SMITH, M., 1995. "The Catholic Church and Public Policy in the European Union," Paper presented at the 23th Conference of the SISR, Quebec.

LOPES, P., 1986. "Le pélerinage à Fatima: processus de transaction entre tradition et modernité à partir d'une situation migratoire," Social Compass, 33 (1).

LUHMANN, N., 1990. Essays on Self Reference, Columbia University Press, New York.

LUNEAU, R. et LADRIERE, P., 1989. Le rêve de Compostelle: vers la restauration d'une Europe Chrétienne? Ed. Centurion, Paris.

LYOTARD, J- F., 1979. La condition post-moderne, Ed.de Minuit, Paris.

REMY, J., 1990. "La hiérarchie catholique dans une société sécularisée," Sociologie et sociétés, vol.XXII, 2, pp. 21-32.

ROBERTSON, R., 1992. Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture, Sage, London.

TOURAINE, A., 1990. "A critical View of Modernity," International Congress of Sociology, Madrid.

VOYÉ, L., 1988a. "Subsidiarity from a Sociologist's Point of View," The Jurist, vol.XLVIII, pp. 292-297.

---- 1988b. "Du monopole religieux à la connivence culturelle en Belgique: un catholicisme hors les murs," L'Année Sociologique, 38, pp. 135-167.

---- 1992. "Popular Religion and Pilgrimages in Europe," Publication of the "Pontificium Concilium de Spirituali, Migrantium atque Itinerantium Cura," Rome.

VOYÉ, L. et DOBBELAERE, K., 1992. "Le religieux: d'une religion instituée à une religiosité recomposée," L.VOYE, B. BAWIN-LEGROS, J. KERKHOFS, K.DOBBELAERE, Belges, heureux et satisfaits: Les valeurs des Belges dans les années 90, Ed. De Boeck, Bruxelles.

WALSH, M., 1989. The Secret World of Opus Dei, London.

WILLAIME, J-P., 1975. "Le Protestantisme face à la construction de I'Europe," F. Alvarez-Pereyre ed., Le politique et le religieux, Peeters, Louvain.